Tagged: collage

From the Mouths (and Hands) of Babes : The Student Arts Expo 2013

by Reggie Rodrigue

The latest post from the Acadiana Center for the Arts Blog is up! It’s on the Student Arts Expo which took place earlier this month during Artwalk. It’s also a treatise on the vital roll that arts education plays in Lafayette Parish’s schools! There’s also a story in there focusing on the most incredible student arts project ever – at least by my estimation! By the end of the article, you will also be able to determine whether you are more creative than a 2nd grader! Good luck on that one!

If you are interested in reading the article, please follow this link to the Acadiana Center for the Arts Blog!

Pattern Recognition: Stephanie Patton and Troy Dugas at Arthur Roger Gallery

by Reggie Rodrigue

Stephanie Patton, “Intersection,” vinyl, batting and muslin, 2013, 62 x 60 x 4 inches, photograph courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

Troy Dugas, “Rye Whiskey Blue,” vintage labels mounted to paper, 2012, 72 x 72 inches, photograph courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

Patterns. They’ve always held a fascination for us. We divine them from nature. We see them emerge in our own lives. We reconstruct them. We interpret, alter and interpolate them.

In truth, being able to see, recognize and interpret patterns is crucial to the survival of the human species. Without some sort of pattern recognition, no higher-order organism could function or survive or be called a higher-order organism, for that matter. This is because pattern is intrinsically linked to organization. Pattern is in our DNA, our brain structure, along with the rest of creation.

Pattern is also that upon which we build our digital lives and affect change in the real world of the 21st century. In the digital realm, we use complex algorithms – a finite set of mathematical procedures performed in a proscribed sequence – to compute vast amounts of data that would otherwise be impossible to do without algorithms. From these computations, we can begin to interpret patterns in the data. By doing so, we can better understand a pattern that may be an invisible or underlying cause of an issue which confronts us such as climate change, traffic flow or any number of other complex problems that are bigger than one mind can bear.

Currently at the Arthur Roger Gallery in New Orleans, two Lafayette, LA artists who bring pattern to the fore in their own works are exhibiting: Stephanie Patton and Troy Dugas. Within both bodies of work, the two artists begin with a simple premise, a minimum of materials, and a highly repetitive process. However, their finalized works speak to the complexity, beauty and meaning that can unfold from such humble and rudimentary origins.

Stephanie Patton is a multimedia artists who currently lives and works in between Lafayette, LA and New Orleans, LA. She received a BFA in Painting from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in 1993 and an MFA in Photography from the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in 1996. After this, she spent some time living in New York City, engaging in the art scene there as well as taking classes with the Upright Citizens Brigade Theatre, where she honed her skills as a comedian. In 2001, Patton returned to Lafayette, LA and continues to grow her career as an artist as well as an educator. She also became a member of the wildly successful New Orleans artists’ collective, The Front.

Stephanie Patton, “Strength,” vinyl, batting and muslin, 2013, 79 x 79 x 15 inches, photograph courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

Stephanie Patton, “Valor,” vinyl, batting and muslin, 2013, 81 x 81 x 15 inches, photograph courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

Stephanie Patton, “Meeting,” vinyl, batting and muslin, 2013, 55 x 86 x 17 inches, photograph courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

Patton’s exhibition at Arthur Roger Gallery is titled “Private Practice.” The title is now part of a running joke with Patton’s work. Her last exhibition at The Front was titled “General Hospital.” Both titles refer to soap operas/dramas centered around doctors and medical environments.While the thought of naming one’s art exhibition after such processed cheese from television is extremely humorous, there is another point to the titles. They offer a point of entry and a certain amount of accessibility for the viewing of Patton’s Postminimalist works. The titles – with their allusions to drama, tension, sickness, healing and recovery – give viewers a clue that Patton’s works are more than just exercises in design and pattern.

Most of the works on display in “Private Practice” are quilted and shaped wall sculptures composed of white vinyl, batting and muslin, which hover and undulate before the viewer like some sort of hybrid between a cloud, a work by Frank Stella and a mandala. The works are anodyne, yet forceful and rigorous. Patton has found a way to take soft materials associated with rest and transmute them into a series of objects that speak of strength, presence, perseverance, and healing. It is an impressive feat, and viewing these pieces puts one in the frame of mind to think about, not only the more abstract and metaphysical ideas engendered in the work but, also, the thought, time, work, skill and care that went into sewing and composing it.

Stephanie Patton, “Conquer,” Video, 8 minutes 8 seconds, 2013, photograph courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

The real tour-de-force of Patton’s exhibition is a video, however. “Conquer” is 8 minutes and 8 seconds of gut-wrenching pain and claustrophobia followed by sublime relief and stoic transcendence. The video begins with a close-up of Patton’s head, neck and shoulders covered in a tight latticework of band-aids which gives her the look of a badly sculpted, clay bust. She stands before her work “Intersection.” The work acts as a formal backdrop to the action in the video. The action begins with Patton searching for an appropriate band-aid to pull. She finds one, and then … RIP! The pain of the action is palpable, and it just keeps going for what seems like an eternity of band-aid ripping; however, it is riveting. One winces and squirms while Patton steadily removes her dummy mask, keeping time with the sounds of her breathing and those nearly interminable separations of adhesive bandage from flesh. By the end of the video, Patton’s full face emerges from its cocoon. One can almost feel the blood coursing through her inflamed skin. Her wide, watery eyes stare out at the viewer with a startling amount of restraint; yet, there is also much in the way of clarity, openness and beauty in her gaze as well. It’s a brief moment of silent reflection and equanimity … and a challenge to the viewer to move through whatever pain is stifling his/her life into a similar state of unshakable grace.

If you would like to view Stephanie Patton’s video “Conquer,” please follow this link to the Arthur Roger Gallery website.

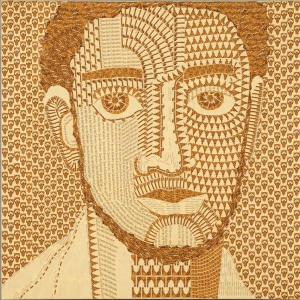

Troy Dugas, “St. Jerome #4,” European liquor labels on paper, 60 x 60 inches, 2012, photograph courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

Troy Dugas, “Fragancia,” cigar labels on cut paper, 47 x 47 inches, 2013, photograph courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

Speaking of unshakable grace, artist Troy Dugas has that in spades as well. One needs such things to produce work at the same caliber as Dugas’ vintage label collages.

Dugas graduated with a BFA from the University of Louisiana at Lafayette in 1994. In 1998, he received his MFA from the Pratt Institute. He currently lives and works in Lafayette, LA.

Early in his professional life, Dugas began working with a particular form of collage that involves using duplicates of the same image, rather than the usual pastiche of dissimilar images and materials that typifies most collage. To put it in mathematical terms (which somehow seems fitting), if the usual form of collage is a process of addition, then Dugas’ form of collage is a process of multiplication – amplifying a single element into what seems like an ecstatic, geometric infinity of pattern. In earlier works, Dugas used identical, vintage prints of ships at sea and flower arrangements to create images that mimicked what one would see if one were to look at the original images through a prismatic lens or the compound eyes of an insect.

Today, the focus of Dugas’ work is on creating abstract designs, second-hand portraits and still lifes with large quantities of vintage product labels.

Dugas abstract works mimic sacred geometry, calling to mind the sort of patterns one would find in a church, mosque or temple. From afar, they take the form of mandalas and are quite meditative in their overall impact.

For the uninitiated, the shock comes when one realizes that these exquisite works are made of old labels for liquor, cigars, fish and canned vegetables, among other commodities. At first, discovering this is a wonderful surprise; however, if one thinks about the meaning behind such work long enough, one reaches a gray area where marketing and spirituality rub shoulders a little to comfortably with one another. This forces one to wonder whether these are glorified advertisements or the sincere works of an artist on his own spiritual path. Personally, I tend to think the latter is closer to the truth.

In an age where everything, including our own digital lives on social media websites, is a product to be marketed and advertised ad nauseum, it is difficult to find a space for reflection and spiritual pursuit that eludes the dictates of “the market.” While Dugas’ works are certainly part and parcel of the overall system of capitalism (they are being sold at New Orleans’ poshest gallery after all) and are composed of the refuse of this system, they still manage to take the viewer somewhere beyond the daily grind of consumption – a space of pure, Platonic freedom.

Dugas is involved in a game of extreme subversion. He begins a work with a pile of the lowest form of art and creates something wholly ineffable and transitive. In the context of our time, there is something truly transgressive about Dugas’ work in that it exudes skill (countering the prevailing rubric of “deskilling” in art today), it obviously takes much time and patience to complete it (two things of which most people have very little these days), and most importantly it turns pop culture and pop art on its head. Given enough green bean labels and time, Dugas can create a work of art on par with a Byzantine mosaic or a Buddhist mandala. He metaphorically takes Warhol’s soup can and runs with it in the other direction. By slicing and dicing commodity labels into a million little pieces and recontextualizing them, Dugas points to a way out of the consumerist paradigm by diving right into and through it.

Troy Dugas, “Fayum Clos du Calvaire,” European liquor labels on wood panel, 48 x 48 inches, 2012, photogrpah courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

However, Dugas has recently decided to go in other directions as far as the type of images he produces. His “Fayum” series is a case in point. The product labels have remained a constant and pattern still plays a key role in shaping the work, but Dugas deploys these to compose representational images which riff on the tradition of Coptic Fayum painting. This type of work flourished in Egypt during the Roman occupation of the country at the tale end of the Roman Empire.

Fayum paintings were typically made of encaustic or tempera on wood panel, and they represented living portraits of deceased individuals. These portraits were painted during an individual’s lifetime, displayed in his/her home, and then placed over the head of his/her mummy as a reminder of what the deceased looked like when he/she was alive. Fayum paintings were basically the Graeco-Roman innovation on the ancient Egyptian funerary mask.

While unequivocally beautiful, Dugas’ “Fayum Series” complicates an already complex and hybridized tradition. These works have a particular sort of resonance for our time, bringing to mind the collapse of a civilization (possibly our own included); the atemporality of our digital age where information, ideas, art, and design from vastly different eras coexist through various media simultaneously and are equally valued; an exploration of the colonialist impulses of much modern art such as Picasso and Matisse’s osmotic response to African art and our own colonialist polemics in the Middle East today; and a porous view of individual identity. Beside the infiltration of corporate logos in these works replicating ancient funerary paintings of people who actually were alive at one point in time, Dugas throws another conceptual monkey wrench in the proceedings by basing some of the works in the series on contemporary arrest photographs found on the internet. It’s a chilling touch that begs viewers to answer the uncomfortable question of what posterity and history have in store for them.

Troy Dugas, “Still Life Cactus,” assorted labels mounted to wood panel, 28 x 35 inches, 2013, photograph courtesy of Arthur Roger Gallery

The specter of modernism haunts Dugas’ “Still Life” Series a little more lightly than his “Fayum” Series, if no less significantly. Here, Dugas breaks with his convention of using a single type of label. He employs an unprecedented assortment of labels to approximate the varying colors, textures and techniques utilized in modernist still lifes. Dugas’ obsessive technique seems to loosen in these works, affording them a sense of playfulness and breezy, if scattered, sensuality.

Together, Patton and Dugas’ current artworks afford viewers vital insight into the ways pattern can be more than simple decoration. Before the onset of modernism and postmodernism in Western culture, there was much meaning invested in pattern. Viewed as symbols of status and origin, pattern was used as a tool to visually order and label the world around oneself. Because of this, every pattern had a fixed meaning. This view of pattern generally broke down under the influence of the modernist impulse to purge symbolism from visual culture. Postmodernism then relegated pattern to being a handmaiden to style and design. The beauty of the contemporary use of pattern is that now it has a freedom of use unafforded to it in the past and it can carry a plethora of meanings depending on its contextualization. This is because we approach pattern from a multitude of different perspectives in our own contemporary moment.

With Patton and Dugas, we have two examples of contemporary artists reinvigorating past forms and materials within new contexts. Their works hold the mirror up to our own complex lives in subtle yet profound ways, unearthing and reflecting undercurrents and patterns of reality. We are given the responsibility of recognizing the patterns and determining their significance.

Stephanie Patton’s “Private Practice” and Troy Dugas’ “The Shape of Relics” are both on view at the Arthur Roger Gallery in New Orleans until April 20, 2013.

It’s all so meta: Cece Cole’s “Thinking about Meditating” on Pelican Bomb!

Oh, Metaculture! It’s like having your cake and eating it, too – or having it shoved in your face! It just depends on whether your glass is half full of bitter irony or half full of sweet sincerity. My glass is filled to the brim with Irish coffee! Anyway, here’s a quick meta-review of a meta-exhibition: Cece Cole’s “Thinking about Meditating” at the Acadiana Center for the Arts and on the pages of Pelican Bomb!

And here are some more pictures of the works in the exhibition shot by yours truly!

All works in “Thinking about Meditating” are by Cece Cole and untitled.

And if you’re interested in reading more on metaculture, check out www.metmodernism.com!

And here’s some more links to get you in that oh-so metamood:

* “Round and Round” by Ariel Pink’s Haunted Graffiti

* “I Am the Antichrist to You” by Kishi Bashi

* “Sun in Your Eyes” by Grizzly Bear

* “I’ll Believe in Anything” by Wolf Parade

Eugene Martin at the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art on Oxford American

Eugene Martin

“A Great Concept”

1987

My fourth article for Oxford American has hit the virtual news stand! It’s about the current mini-retrospective exhibition “The Art of Eugene Martin: A Great Concept” at the Ohr-O’Keefe Museum of Art in Biloxi, MS. Martin is one of the largely unsung heroes of Southern Art, and the article discusses his life, his work and the exhibition itself. It’s a truly inspiring read if I do say so myself – check it out here.

Chris LaBauve at the Warehouse on Garfield

Chris Labauve

“Standing on a Crack”

singed cigarette butt collage

Chris LaBauve

“Digging for Gold”

acrylic on cigarette packaging collage

Chris LaBauve

“Untitled”

archival glue and ink on wood

on view in the group exhibition at the Warehouse, 625 Garfield St., Lafayette, LA for the month of November 2011

*** Author’s note: To read a review of this exhibition, please see the the post titeled “Off the Beaten Path at the Warehouse on Garfield” here.

Pat Phillips in “Revolution No.63” at Parish Ink

Pat Phillips

“NOMAD”

acrylic, ink and aerosol paint on canvas

Pat Phillips

“Homework 1”

pen, aerosol paint and collage on wood panel

Pat Phillips

“Homework 2”

pen, aerosol paint, collage on wood panel

on view in the group exhibition “Revolution No.63″ at Parish Ink, 310 Jefferson Street, Lafayette, LA 70501

*** Author’s Note: If you would like to read the review of “Revolution No.63,” please see the previous post on this site titled “Free Wheelin’ It: ‘Revolution No. 63 at Parish Ink” here.

Our Lady of Global Conscience: Lynda Frese at the ACA

Lynda Frese

“Introitus”

mixed media collage

2010

Lynda Frese

mixed media collage

2011

Lynda Frese

“Panarea”

mixed media collage

2009

Installation shot of Lynda Frese’s “PACHA MAMA: earth realm”

Installation shot of Lynda Frese’s “PACHA MAMA: earth realm”

by Reggie Michael Rodrigue

What is a cave? For most of us today, a cave is simply a large hole in the ground with a range of unpleasant inhabitants we’d rather not think about or come into contact with: bats, roaches, snakes, rats, bacteria, etc. Caves are cold, damp, and dark places. We generally have little use for them. However, our ancient ancestors did. They used caves as places of refuge. They used caves as places of worship and ceremony. Our ancestors believed that caves were ideal locations for making, using and displaying their sacred art. One could make a convincing argument that civilization itself was born in caves. Our ancestors definitely had a strong attraction to them, and they thought of them as much more than big holes in the ground. They respected and beatified them. The cave was the “Earth Mother” embodied in rock. Our ancestors drew parallels between caves and female genitals. Life, as they new it, came from both.

It may seem like a strange confluence to us today, but our ancestors saw everything in nature as being alive and connected to everything else. Over the course of our history as humans, many of us have lost this rich way of seeing the world. In the last 3000 to 4000 years, the importance of nature has shrunk in our collective esteem. Monotheism dealt the first blow, restricting believers from worshiping nature deities. The Renaissance dealt the second, ushering in the age of “man as the measure of all things.” The empiricism of the Age of Reason taught us to break down things and relationships to their smallest parts and clinically analyze them separately. The Industrial Revolution sent us hurtling even further away from nature. This was when man truly began to exploit the world around him to meet the needs of growing national economies. Ever since then, modern man has typically held nature in contempt or viewed it as a commodity to be infinitely harvested, bought, sold and exploited.

Today, we are beginning to see the fruits of such a view of nature, and they are rotten on the vine. Widespread pollution and deforestation are wreaking havoc on the delicate ecology of the planet we inhabit. If we maintain the trajectory we are on at this moment, collapse is inevitable. Throughout human history, there have always been stories of apocalypse or instances of great destruction at the hands of “God” or nature. Today, we may be on the verge of an apocalypse of our own making.

This is why it’s vital for brave and conscious individuals to sound the alarm – to warn others of what we are doing to the planet and ourselves before it’s all for naught. Artists (we are an idealistic lot) are generally up for such a challenge. One, in particular, is University of Louisiana, Lafayette art professor Lynda Frese.

“PACHA MAMA: earth realm” is Frese’s current wake-up call in the Side Gallery of the Acadiana Center for the Arts. In this exhibition, Frese offers viewers a stirring body of multimedia collages that speak to the connection between man and nature. To create these works, she mixed her own photographic images of ancient, sacred sites around the globe with found, antique prints. Frese then painted egg tempera (a compound made of egg yolks and natural pigment) on them to add more depth or detail to the collages. Metal foil, such as gold leaf has also been added in some of these works. The egg tempera and the metal foil impart an ethereal luster, yet they both draw the viewer back to thinking about the richness and bounty of the earth. Frese learned how to use egg tempera and metal foil from a series of residencies in Italy in which she studied Renaissance art. During one of these trips, an Italian friend/colleague gave her the pigments that were used to tint the egg tempera in this series. They are reportedly a century old. Trips and yoga retreats to India, South America and Northern Europe also influenced this body of work.

What makes the “PACHA MAMA” series so resonant is the way the media mirrors the imagery and content of the work. The series is an exploration of the richness of the heavens and the earth, as well as the sacred sites and objects that man has made to connect to and interact with them. Frese taps into the spiritual dimension of the work through a dreamlike juxtaposition of images and symbols ranging from stone menhirs, botanicals, a sphinx, forests, cathedrals, birds, pre-Columbian statuary, the Virgin Mary, woodsmen, mountains, burial sites and human remains, Dante’s Inferno, vessels and jars, sunlight, the Tree of Knowledge, organs, a lion, eggs, a lotus, snakes, sacred hearts and Christian icons, soldiers and war, along with many references to fire and water in the form of rivers, lakes, springs and seas. Fire and water here represent spiritual purity, yet the also represent absolute destruction in certain apocalyptic images. Frese is truly concerned with the way we pollute and misuse the waters of our planet. Using a bit of artistic karma, Frese depicts ravaging floods consuming the world. It is an act of cleansing, clearing the way for the next age. In this sense, apocalypse is both a cataclysm and a revelation of the truth lying dormant underneath man’s occasional stagnation in thought and action. The scale of the imagery is overwhelming and monumental, much like the reality of our world, the universe and time itself. Yet, Frese has chosen to keep these works intimate and precious in size. It’s as if she is saying, “This is your world and your reality. You own it. Take care of it before it’s too late.”

This idea of time ticking away runs through the exhibition. There are no images of clocks present, yet each work can be viewed as a slice of time in the ongoing saga of our relationship with the world. By the same token, the accretion of disparate images (contemporary photographs of ancient works that are now global heritage sites, new photographs of jungles and soldiers in modern conflicts, antique prints, contemporary flourishes made through the use of media that were used primarily during the Renaissance) speak of the contemporary notion that the march of time is only an illusion we perceive. The current view that contemporary physicists take on the nature of time is that it really doesn’t exist, at least not in the form that we perceive. This is a paradox with which we must contend. Frese’s “PACHA MAMA” series addresses this directly, displaying our perception of discreet moments, while speaking of the epochal cycles of nature as well as exposing the fact that the past, the present and the future are all taking place simultaneously in the infinite now.

Standing before these discreet works and gazing into their seemingly inexhaustible depths, one is overtaken by the sublime. The experience is one of beauty and terror, love and death, earthiness and cosmic ecstasy – eternity in the guise of a series of diminutive collages on walls. They silently shout for a reassessment of our short-sighted priorities. They state that our position in this world should be one of humility but also one of empowered stewardship.

Of late, a handful of philosophers have been discussing a shift in our global mode of thought. For approximately the last 50 years, we have lived in a world that has been described as postmodern, and our art has reflected this. The period was marked by a tendency to deconstruct meaning, to eradicate the notion of subject or narrative, to view history as dead, to tear down hierarchies and replace them with lateral strategies meant to devalue the subjective experience of the individual, to favor spectacle over substance, and court irony and cynicism as a mode of thought and a way of life. The period also ushered in a much needed conversation about the importance of women and minorities in our society. Postmodernism brought them to the table, so to speak. Now, however, we seem to be moving into a period that is being touted as “metamodernism.” It is a consolidation of the modernist and postmodernist positions, which court both irony and feeling simultaneously. The subjects of love, sincerity and hope are returning to the fore as a balm over the postmodern malaise. Narrative structures and figuration are also being introduced back into art. However, we are doing so in a more worldly and knowing way. Irony isn’t dead. It’s just tempered by its exact opposite. In a sense, we are rebuilding what we tore down in a new image based on the resolution of paradox and dichotomy. It is a more complex view of the world that takes all positions into account as valuable and life affirming.

There is something about Lynda Frese’s current body of work that meshes with this concept of the metamodern. The works are definitely cut-ups and pastiches analogous to postmodern sampling. Yet rather than breaking down meaning, they re-engineer it. They infuse collage with substance, purpose, narrative and feeling. The overall effect, due to the over-painting of egg tempera and metal foil, is one of cohesion, rather than the usual effect of collage – dislocation. At the same time there are moments of postmodern irreverence. Two of the images include “googly eyes,” the small plastic craft supplies used to imitate eyeballs. They act as instances of humor injected into some otherwise serious and profound work.

Adding even more layers to Frese’s enterprise, the exhibition also has a book to accompany it. The book shares the same title as the exhibition. Within it, beautifully rendered photographs of the individual works in the “PACHA MAMA” series are paired with occasional poems by Louisiana poet laureate Darrel Bourque, who is also a professor at the University of Louisiana, Lafayette. Within the structure of Bourque’s poems, he explores the images present in certain works, bringing an extra layer of sublime narrative and insight to them. The book also includes short essays by friends Kathi von Koerber, a dancer/healer/filmmaker, and Michele Baker, a yoga instructor, as well as a personal essay from Frese herself. The book is currently on sale at the front desk of the Acadiana Center for the Arts for $25.00.

In conclusion, I highly recommend a visit to the Acadiana Center for the Arts for an introduction to Frese’s “PACHA MAMA” series. It’s one of the most compelling, engrossing, mind-expanding, soul-nourishing, awe-inspiring and beautiful bodies of work I’ve seen in recent memory. You’ll never look at a cave, a forest or the sea in the same way ever again. It’s all about synthesis and really seeing the universe as a unified system in which discreet thoughts and actions manifest in ripples that, over time and space, amount to seismic shifts in consciousness and the nature of reality that feed back into the fabric of eternity. Make the connection.

Dawn DeDeaux in “Prospect Lafayette”

Dawn DeDeaux

“Same Place, Different Time”

photographs on reflective foil

2008

on view in the satellite exhibition “Prospect Lafayette” at the Acadiana Center for the Arts, Lafayette, LA until January 29, 2012 as a part of the Prospect New Orleans 2 Biennial.

*** Author”s note: To view a review of “Prospect Lafayette” on this site, click here.

Hannah Chalew in “Parallel Play” at T-Lot

Hannah Chalew

“Relict Landscape”

rebar, soil, wisteria, catsclaw, thread, wire, mesh

2011

Hannah Chalew

“Odin St. Takeover Part II”

pen and ink on painted paper, wood, chicken wire, soil and creeping fig

2011

Hannah Chalew

“Threshold”

pen and ink and marker on paper

2011

Hannah Chalew

“Intertwined”

pen and ink on paper, thread and pins on canvas

2011

on view in the group exhibition “Parallel Play” at T-Lot, 1940 Saint Claude Ave., New Orleans, from Friday, October 14 at 6:00pm – Tuesday, January 31, 2012 at 10:00pm

Author’s note: To read a review of “Parallel Play” at T-Lot, go to the previous post titled “Our Backyard Kicks Your Backyard’s Ass: ‘Parallel Play” at T-lot” here on “louisianaesthetic.”

Mary Ellen Leger at the ACA

Mary Ellen Leger

“Braille Series #28”

acrylic, braille pages and printer’s ink tins on wood